I’ll never forget the first time I heard “Pop Goes the Weasel” in a collection of archival Edden Hammons tunes. That tune got me thinking about the origins of the old-time fiddle repertory as a whole—after all, it’s not a tune I would expect to hear from a West Virginia mountaineer born in the 19th century. But that was before it slowly dawned on me that old-time tunes had to come from somewhere, and if not composed within the tradition, then where did they come from? Once you think about it, it becomes obvious. Depending on geography, one can hear the echoes of global foundations in our old-time fiddle music, as well as popular music, minstrel pieces, broadsheets, and cowboy ballads in the songs. But today, there seems to be a kind of heavy inertia that mandates a certain sound and a predetermined set of music that is defined as “old-time.” Of course there are complexities to this concept (if indeed it exists) that are best debated elsewhere, since this is a review of the latest album from Molsky’s Mountain Drifters.

My point is this. The frequent injection of new tunes and obscure old material into the old-time repertory is a good thing. And no one does it better than this trio. Their second album, Closing the Gap, bravely and boldly continues down the path they pioneered with their self-titled first record. Fiddler Bruce Molsky seems to relish the idea of bringing new material into the fold. He has stated that he wants the band’s music to point to the future of traditional, rural music. “I was looking for a new voice,” says Molsky, “A new avenue of expression using old time mountain music as the jumping-off point, but not being constrained by hard core traditionalism.” It’s not the first time, for he already has under his belt some side projects that fuse Scandi-trad, Celtic, and other world musics onto an old-time foundation.

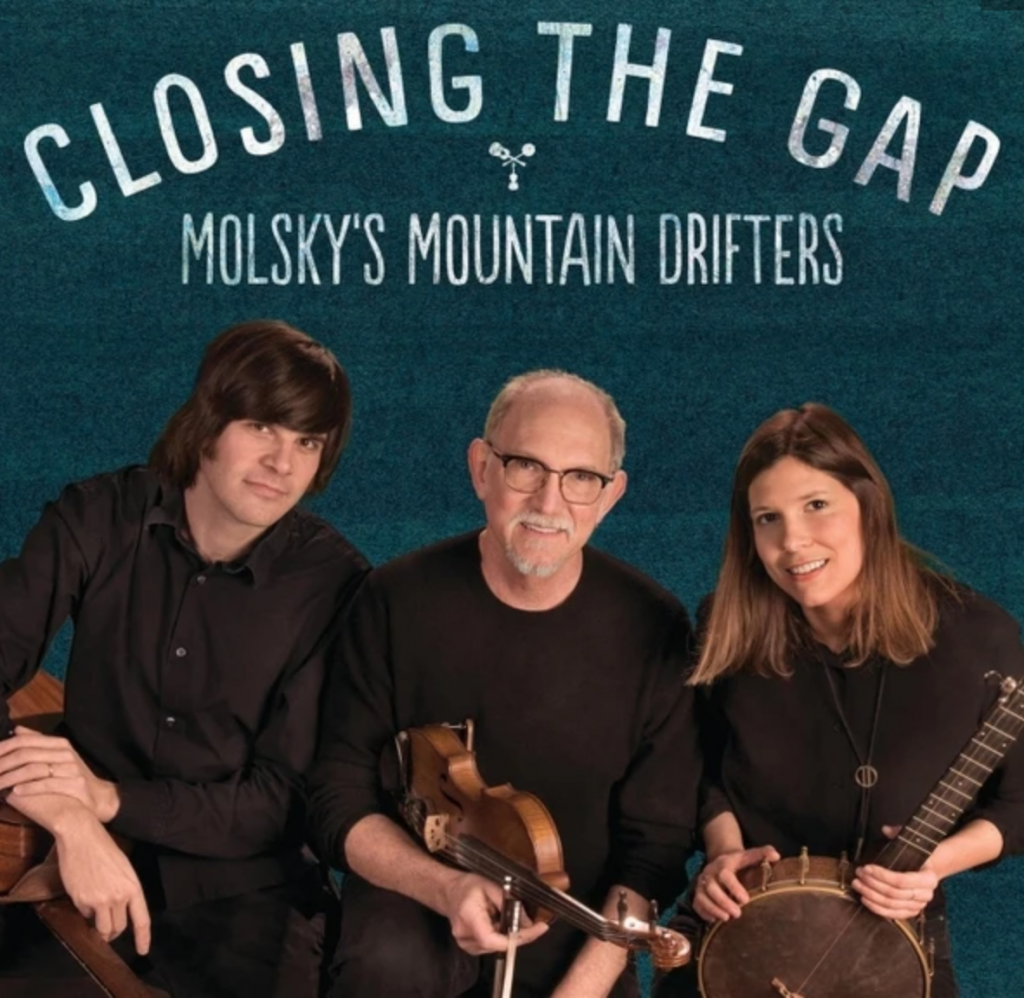

Along with Bruce Molsky, the Drifters are made up of Allison de Groot on banjo and Stash Wyslouch on guitar, solid and inventive pickers and vocalists who do a stellar job of both supporting and inspiring the veteran fiddler. Molsky was a Visiting Scholar at the American Roots Music Program at Boston’s Berklee College of Music when he first met Allison, who grew up in Winnipeg, Canada. Boston-based Stash Wyslouch got his start as a guitarist in metal bands, and he brings a wild energy to the band, pushing the envelope with innovative rhythms and tunings. His bass runs fill in the bottom end of the mix with a complexity that makes me forget there is no bass player here.

The album opens with “There’s a Bright Side Somewhere,” a wistful old piece that eerily foreshadows the momentous and devastating events that were soon to come in the spring of 2020. Some of my favorite tracks include “Sweet Bride,” an old-sounding waltz composed by Northern English singer Kate Rusby, who is a superstar in the world of Celtic folk music. The album’s title track, made by Allison, is a growling, raging modal reel that would sit just as well in an Irish pub session as in a dark hollow somewhere in North Carolina. This record contains a fair share of joyful, impeccable harmonies as well as the red-hot barn burners we would expect from a trio of this caliber.

“The Little Carpenter” is an old ballad that’s reinvigorated by the injection of Stash’s unusual strum pattern. Molsky previously recorded this one with Mozaik, and it was also covered by the New Lost City Ramblers as well as Uncle Earl. The first known recording was made in 1937 by a blind fiddler named Jim Howard in Harlan, Kentucky, recorded by Alan and Elizabeth Lomax. But this one goes WAY back. The first publication I could find was in William Henry Long’s Dictionary of Isle of Wight Dialect (England) from 1886 and titled “The Little Cappender.” W. H. Long was from a West Wight farming family and the songs he includes in his Dictionary were apparently “collected from the mouths of the peasantry” on the island in the early part of the nineteenth century.

“The Graf Spee,” a four-part reel, comes directly from the contemporary Irish session world. On the surface it is often thought to be named for a famous German battleship from WWI, for indeed the ship did bear the same moniker, but for scholars who love to dig below the surface, the tune’s title has a deeper story. No other tunes in the Irish repertoire are named after modern battleships, and its unique occurrence was odd enough to arouse the interest of researchers such as Brendan Breathnach and Matt Seattle. They found the same tune in the Gunn Book (Fermanagh, 1865) as “The Grand Spy.” This was in all likelihood a corruption of a still older title, “Grant of Strathspey,” composed by Scotsman Robert Bremmer (c. 1713-89). Bremmer published the earliest collection of specifically Scottish dance music around 1760. The title honors the Grant family, who long controlled a portion of the River Spey in the Scottish Highlands. Castle Grant on Speyside was the main residence of the clan from 1693. Over the years, the tune morphed from a strathspey into a reel, gained a fourth part, and changed its title.

What a perfect metaphor for the evolution of the music we love. From the Scottish Highlands to the Isle of Wight, from a metal guitarist to “Pop Goes the Weasel,” our music thrives on cross-fertilization. The proof is on this record for all to hear.

A Magazine Dedicated to Old-Time Music

Search The Old-Time Herald

Footer

Contact

The Old Time Herald

PO Box 61679

Durham, NC 27715-1679

Phone: (919) 286-2041

Email: info@oldtimeherald.org

Leave a Reply