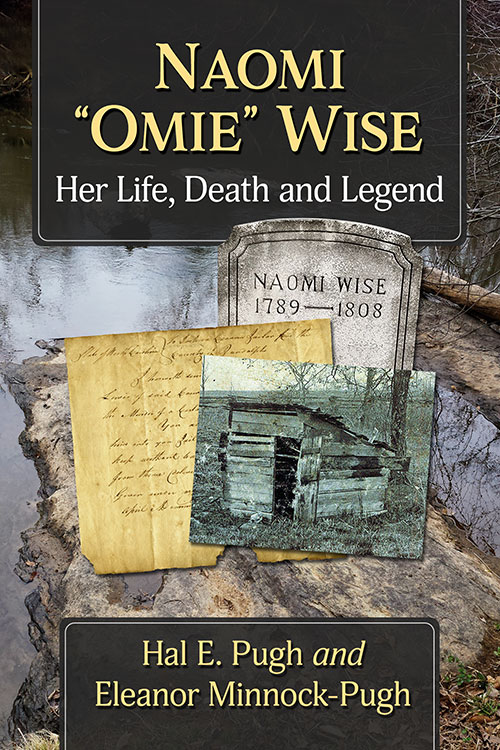

Naomi “Omie” Wise: Here Life, Death and Legend

by Hal E. Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh

“Greedy girl goes to Adam’s Spring with liar; lives just long enough to regret it.” That’s Harry Smith’s acerbic summary of “Ommie Wise,” from the notes to his Anthology of American Folk Music, an unsentimental take on a history that, as the authors of this detailed volume point out, lent itself to a variety of sentimental posturing. Naomi Wise, their research shows, was no romantic heroine, hardly innocent, probably not beautiful, certainly not refined, none of which matters at all in the light of her suffering (nor was she notably greedy, although she may have been naïvely determined to take her chances with the man she hoped would better her status). Those are the qualities that the romantics and moralists in song and in print have used to fit her up, a jury-rigged object of disapprobation or pity. As long as poor Omie Wise is in their spotlight and the social circumstances of her murder just a shadowy backdrop, as long as we see her in the long tradition of the murder ballad as one victim whose weakness put her in the power of one unscrupulous man, we’re safely in the world of morals and sentiment. But Naomi’s home place was no more moral and no more constructed of sentiment than ours is, and the achievement of this book is to make clear just how relentlessly confining the real architecture was.

The story seems simple enough. Naomi Wise, a servant, already the mother of two illegitimate children, becomes pregnant by a neighbor of higher social standing; rather than accepting the diminishment of his own prospects by the revelation of their liaison, he lures her off on a journey that she thinks is an elopement but isn’t, takes her to Deep River, overpowers and drowns her. The ballad tells us the steps she takes, from seduction to betrayal to the rock at the water’s edge where she will be laid out for her inquest—but it doesn’t tell us what this book does in fascinating detail: how the way she followed was as much a public works project as a desire path. In the communities where Naomi lived and worked, illegitimacy was common enough to have been formalized through the “bastardy bond,” a legal document requiring that the father of an out-of-wedlock child be named and post a bond to indemnify the public from any expenses. If the mother would not identify the father, she might be fined or imprisoned; even her very young children, if it was determined that she could not support them, might be taken from her and bound to an apprenticeship. Combine this with a standard of sexual behavior that considered poor women fair game for men of means, and you could hardly come up with a more hazardous set of legal and social circumstances. Naomi’s lover had no more qualms about sleeping with her than he had intentions to marry her; if social disapproval or financial obligations threatened to inconvenience him intolerably, he had only two courses of action when the law ordered Naomi to name him as father: he must buy her silence or he must enforce it.

Naomi—out of naivety or ambition or perhaps because, after her two previous lovers had bailed on their responsibilities for the children she’d conceived with them, she was simply fed up with taking all of the weight on herself—wouldn’t keep the secret. What her murderer hoped to settle privately and quietly would become a matter of public record. And public records form a good deal of the documentation that this book provides, filling in not just her story but the context of legal and social expectations that made the murder if not inevitable then at least as likely as any other outcome. Seeing the words Bastardy Bonds at the top of a printed form, with blanks for the father’s and mother’s names and for the name of the county to be indemnified for child-rearing costs, or the apprentice bond (another fill-in-the-blanks pre-printed document) for Naomi’s orphaned son, off to become a hatter at eight years old, makes it clear at once how commonplace Naomi’s situation must have been and how little privacy or even scandal mattered in comparison with the state’s desire to protect itself from expense. The leverage brought against an unwed mother to force her to divulge the father’s identity was primarily financial and entirely remorseless. That this pressure might be relieved only by confession or self-sacrifice or death was as much a matter of law as of offended propriety.

If a knowledge of 19th-century legal matters may not seem like the stuff of ballads, that’s at least partly the point. Pugh and Minnock-Pugh spend plenty of time with the words and sources and provenance and variants of a song that has become part of the common stock of folk narratives, but they also consider the insights offered by two literary treatments of the murder, a folk poem found in the commonplace book of Mary Woody and the account, first published by Braxton Craven in The Evergreen, a literary journal. Both Craven and the author of the poem treated Naomi Wise as a matter of sentiment and her murder as a lesson in practical morality and as an occasion for the safely distanced sorrow of melodrama. But they also had a more personal stake. The unknown author of the poem included information that suggests a more-than-casual familiarity with the circumstances surrounding the murder; the poem “gives a very detailed description and account of those involved and of the locale of the murder, and offers an intimate look into Naomi Wise’s life and details about what happened prior to and after her body was found in Deep River. Perhaps most significantly, it gives us a rare unfiltered view of morality as seen through the perception of a woman in early 19th-century North Carolina.” Despite its rough-and-ready versification, the poem is a cache of local knowledge; although its author hasn’t been identified, the Woody family was closely connected “by kinship and proximity to many of the people directly involved.” Braxton Craven, author of “Naomi Wise, or the Victim,” eventually president of Normal (later Trinity) College, drawing on the oral history of the community, may have produced a “heavily romanticized and theatrical” account of Naomi Wise’s story, but he had his reasons. He was himself the child of an unwed mother and had been farmed out to a nearby family. “His sympathy,” Pugh and Minnock-Pugh write, “for Naomi Wise, a fellow orphan, was clearly deeply personal, and it would seem that he understood how Naomi’s circumstances….cast her to the bottom of the social order.”

The connections don’t end there. Residents of the same Randolph County where Naomi Wise died, potters living on the land once owned by Quaker potter, William Dennis, a witness for the prosecution at the grand jury that indicted Wise’s suspected murderer, the authors of this book bring local knowledge and local understanding to their research, and there’s nothing sentimental about their conclusions. This is carefully documented, engagingly written history, as clear-eyed in its account of a society whose laws protected the pockets of the powerful as it is sympathetic to the disenfranchised people these laws made even more vulnerable.

Leave a Reply