“These beautiful and honest photographs take me back,” writes Alice Gerrard in her brief, heartfelt introduction to John Cohen’s Speed Bumps on a Dirt Road: When Old Time Music Met Bluegrass, “to a time when we were driving full tilt into a new world of amazing music, days and nights of discovery, friendships across many lines….” The lines that the photos in this book cross are generational (from the Carter Family to a young banjo student of an elderly Cohen), cultural (an auction in Hazard, Pete Seeger in a TV studio, Amish farmers listening at a bluegrass festival), in one case racial (Muddy Waters), but memory is only one point of intersection, although it is reason enough to value this book. Cohen was always more than a recorder of the past or its representations. A thoroughly trained artist, acquainted with de Kooning as well as Bob Dylan and Doc Watson, Cohen brought to his photography the same insistence on immediacy that drove his work with the New Lost City Ramblers. As Ray Allen explains in Gone to the Country: The New Lost City Ramblers and the Folk Revival, what Cohen wanted was to capture the energy of the old recordings that brought him to country music in the first place.

On the page facing Alice Gerrard’s note, Grandma Davis, of Roaring River, North Carolina, her fiddle slanting downwards from her shoulder nearly in playing position, her bow arm resting on her knee and her hand clutching the frog, her face turned from the viewer and her hair hidden by a scarf, looks out the window past a birdfeeder and a light-colored car. That we can’t be sure what she is seeing only adds to the intensity of the moment. The camera is angled so that the slats of the wall run downhill from left to right, not quite in parallel with the line of the window frame or the partially visible porch roof, not quite in parallel with the neck of the fiddle. The bow, though, angles upward, as if at cross purposes to every line except that of the fiddler’s back; if the running-downhill slope of the house suggests entropy, the bow and the woman holding it have the rising, enlivening momentum of a good old tune cutting across the ordinariness of any given day.

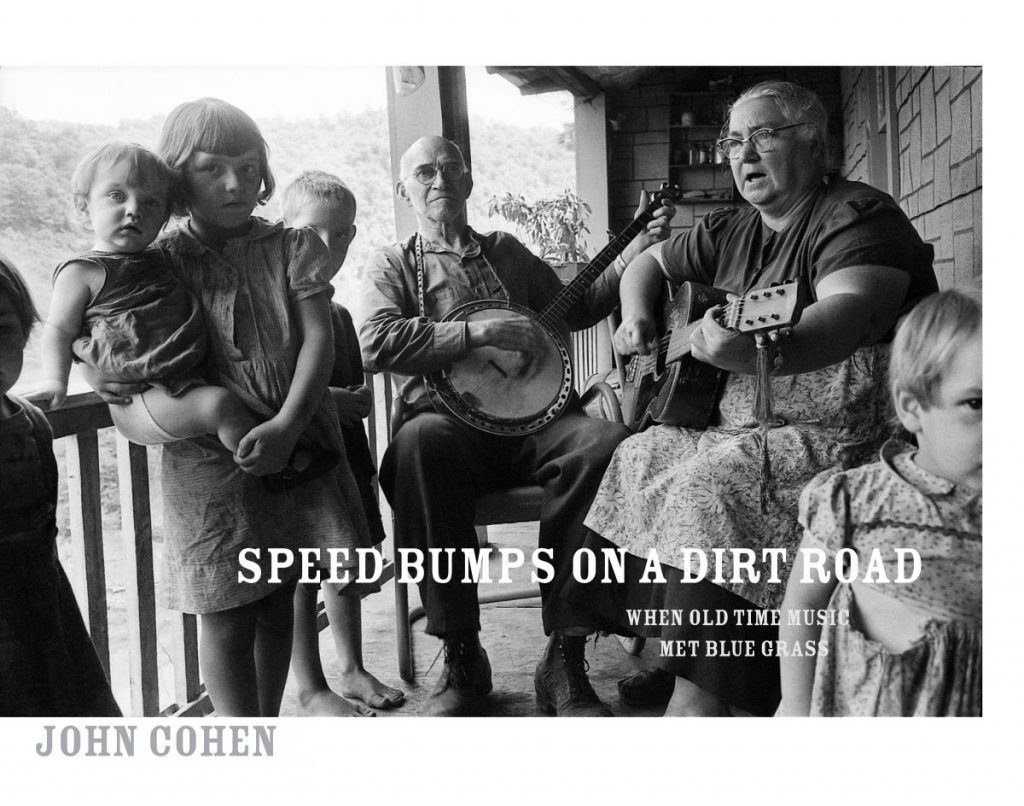

Although the use of a strong diagonal, usually the neck of an instrument, is everywhere in Cohen’s book, this picture is unusual in having no face visible. Cohen’s great gift is portraiture, and the book’s organization into sections whose titles provide all the context necessary (“Old Love Songs & Log Cabins,” “Bluegrass Bar in Baltimore,” “Fiddler’s Conventions” are just the first three) highlights the faces of the folks who took their places before Cohen’s camera. Grandma Davis again, this time playing, looking at her fiddle fiercely, while over her shoulder a girl, cheek resting on one hand, is just as intently lost in the music. Dock Walsh, dressed like a banker or a lawyer in a suit, tie, button-down shirt, plays banjo in the torn plaid backseat of a car; he looks downwards, eyes half-closed, eyebrows alert above his clear glasses frames, a study in concentration. And then there are the wonderful portraits of Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard, some from a recording session and some from the photo session that was used for the cover of their Pioneering Women of Bluegrass compilation. To understand what Cohen has discovered in their faces, in any of these faces, you’d have to listen to their music; to have the photos with you as you listen is to hear newly.

In an interview with Steve Paul at the opening of a show of his portraits of Bob Dylan (available on YouTube), John Cohen tells about photographing Dylan and seeing not Woody Guthrie but “more James Dean, and the contemporary pent-up feelings that young people were feeling at that time that had nothing to do with folk music, and that was a big revelation.” Cohen was seeing not just behind the image Dylan wanted to project, the studiously self-conscious Guthrie imitation, but past the whole dilemma of authenticity and tradition. The Ramblers, Ray Allen writes, didn’t begin with field collection, but with rediscovered commercial recordings; what they found there was the energy of performances that could connect with an audience both as a reflection of the past and as the possibility of work that might be done now. Cohen’s photos bring the past, several pasts—the old ways and their revival in music—to mind, but they also look beyond the present. The book begins with the Carter Family and it ends with shots of Anna and Elizabeth, the Downhill Strugglers, and Nora Brown, that girl with a banjo taking a lesson with Cohen. The Downhill Strugglers, with whom Cohen performed and recorded, are a straight-ahead old-time band. Anna and Elizabeth, starting from their study of the ballad tradition, have made electronic assemblage part of their practice. Who knows what Nora Brown will do with what she’s learning?

Cohen’s mastery of the essentials of photography—the development of a formal and expressive vocabulary, the discernment that singles out the meaningful within the ordinary, the heightened awareness of the momentary, all qualities that musicians and lovers of music will recognize as necessary to their own art—are evident in this book, but even more important is the sense of surprise and recognition that each image offers, in the picture and in the subjects, a glimpse of something beyond skill, beyond representation, almost beyond grasping. That’s what I’ve felt about this music, why I wanted to be in its presence, ever since I first heard the Swamp Root String Band play “Sugar Hill” in a bar in Mendon, New York. That’s why I want to acknowledge the debt we owe John Cohen for what he remembered and held in memory and for what he still makes possible.

Leave a Reply