By now, all readers of the OTH are probably aware of the crucial role that Black musicians played in the creation of what we think of today as “old-time music.” Yet there are very few non-contemporary (and not too many contemporary either!) recorded examples of Black old-time fiddling. In the 1920s, when the music was first recorded, the record companies segregated the music, in order to perpetuate systemic and persistent racism (and of course with an eye towards profits). They classified what we think of today as old-time music as “white” music and issued these recordings in their “Hillbilly” or “Country” series, for white consumers. Black musicians’ recordings were issued in the “Race” category. There are a few, but only a very few, exceptions to this. Thus, the handful of Black musicians who made recordings with whites (such as Jim Booker and Amédé Ardoin) ended up in the “Hillbilly” series, while Black fiddlers including James Cole and Eddie Anthony (who recorded both fiddle tunes and blues) ended up in the “Race” series.

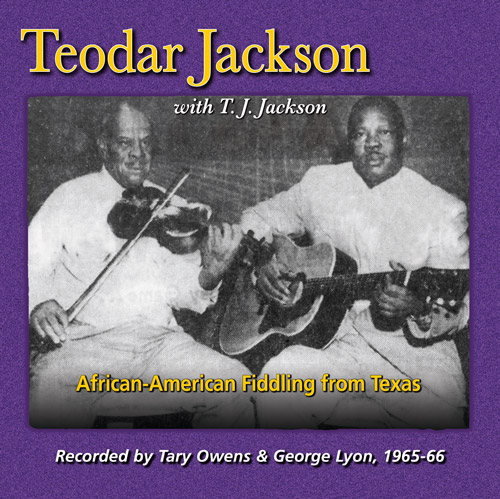

Blues recordings (i.e., recordings of Black musicians) of the ’20s and ’30s tended to be either in jazz band settings, which typically did not include fiddles (as they were unable to compete with horns’ volume), or by solo singers accompanying themselves on guitar. There are, of course, exceptions to this (Mississippi Sheiks, Peg Leg Howell with Eddie Anthony, James Cole and Tommy Bradley, and a few others), but on the whole, very few Black fiddlers were recorded commercially during the 1920s and 1930s. We have relatively few field recordings of Black fiddle music from the pre-War era, and recordings of Black old-time fiddle music after World War II are even rarer. Fiddlers James “Butch” Cage, from Mississippi, and Joe Thompson, from North Carolina, are the most famous examples, because they both performed outside their communities and their recordings were released commercially. In fact, Teodar Jackson was supposed to play at Newport in 1966 but had a heart attack and couldn’t make the trip, so they brought Butch Cage instead, and that’s why we’ve known about Butch Cage but not about Teodar Jackson.

It is true that by the 1950s and ’60s there weren’t many Black fiddlers still active, but who knows how many Black fiddlers may have still been playing in the pre-War era, whose music will never be heard? It is a miracle that we have the recordings on this CD, of musicians from Central Texas whose playing is as strong as any I’ve encountered.

Most of the recordings on this wonderful CD were made by folklorist Tary Owens in the mid- 1960s, when he was a student at University of Texas. A few of the songs were recorded by George Lyon at a live college coffeehouse performance. About 10 years ago, I visited the archives at the University of Texas at Austin, and digitized the Tary Owens recordings; I had to promise not to disseminate the recordings, but I did leave a copy there which was found some years later by Howard Rains. The aural quality on this CD is much, much better. One thing puzzles me, though; my recordings include other excellent pieces that I would have thought worth issuing. Perhaps there will be a Volume 2 someday!

The material here ranges from old familiar melodies (often played in unexpected ways) to blues songs sung in the style of Mance Lipscomb (a friend and associate of Jackson’s) to old-time songs like the “Eighth of January,” “Golden Slippers,” and (one of my favorites) “Drunken Hiccoughs.”

Teodar Jackson’s grandfather migrated to Texas from Mississippi in the mid 1800s, and “Old Aunt Jessie” sounds very Mississipi-ish to me. It’s in the key of C, with phrases repeated for an indeterminate number of times, foot-stomping, and percussive guitar backup. Think Narmour & Smith, or Ming’s Pep Steppers. The fiddle is tuned about a step low and the words are hard to understand, at least for me; those factors lend this piece a mood of mystery.

“Drunkard’s Hiccups” is another standout, an unusual treatment with a fabulous dance beat, with more foot-stomping and the percussive guitar style. “Lost John” is not the usual tune associated with that title; it’s actually “Someday Baby,” a tune widely recorded (including by Fred McDowell, Sleepy John Estes, Big Maceo, and Charles Brown). Similarly, “Mama Don’t Allow” is not the song I think of when I hear that title; it’s actually “My Babe,” a huge hit written by Willie Dixon for Little Walter and recorded by many others, and based on “This Train Is Bound for Glory.”

In “Whoa Mule,” the foot-stomping becomes a gallop while the fiddle makes noises like a mule. Again, this is an outstanding version of an old chestnut. “Ride Your Pony” surely is related to the song by that name that I’ve heard from various Louisiana Creole musicians, as well as to the hit song by Allen Toussaint that was recorded by many New Orleans artists starting with Lee Dorsey. The way Teodar Jackson sings it, you just know he’s lived this song, trying to work with a recalcitrant mule.

There are some guitar pieces here as well. I especially liked the fast-paced E blues instrumental “Out and Down.”

Be sure to check out Dan Foster’s excellent notes, a treasure trove of information (with photos) about rural Black American fiddling and Texas fiddling (on the Field Recorders’ Collective website). We owe our most heartfelt thanks to the late Tary Owens and George Lyon for making these recordings, and to the Field Recorders’ Collective for making them available, more than 50 years later. Very highly recommended.

Leave a Reply