Tony Russell has documented and interpreted a range of American vernacular music traditions for over half a century. Readers of the Old-Time Herald will recognize him as a (or, in the opinion of many, the) leading scholar of country music’s early years—the pre-World War II period generally considered the Golden Age of recorded old-time music. Russell compiled the monumental reference book Country Music Records: A Discography, 1921-1942 (2004), and he wrote the award-winning essay collection Country Music Originals: The Legends and the Lost (2007); additionally, he published and edited the legendary magazine Old-Time Music (between 1971 and 1989). Yet Russell has long been committed to exploring diverse music traditions, with his publications broadly advancing collective understanding of the recording legacies of Black as well as white Americans. He authored, for example, noted studies of blues music, including Blacks, Whites and Blues (1970) and The Penguin Guide to Blues Recordings (2006).

Russell has maintained unfailingly high standards in his research, writing, editing, and cultural advocacy, and it would not be hyperbole to refer to him as a national—or more properly, since he lives and works in the UK, an international—treasure. This reviewer—having collaborated with Russell on three Bear Family Records boxed sets of old-time music—witnessed his work being positively received both locally where the featured music traditions had originated as well as globally among far-flung communities of old-time music aficionados. Russell’s latest offering to music fans worldwide—Rural Rhythm: The Story of Old-Time Country Music in 78 Records—is a (if not the) definitive general interest (as opposed to academic) book exploring the canon of prewar old-time recordings. Rural Rhythm vividly portrays the various people involved in the making of 78 rpm recordings while analyzing those recordings in terms of theme, style, repertoire, and performance, and while assessing their historical and more recent reception.

The premise of Rural Rhythm is to offer a curated list of old-time recordings from the period 1923-1940. Readers might be forgiven if they are wary of lists, as conventional and social media outlets regularly offer various and sundry lists—generally with little or no curation—on every imaginable topic (usually as guilty-pleasure entertainment or as a ruse for targeting ads to unwitting readers). And even those music industry lists that are intended to be received with a measure of respect—halls of fame, registries, Rolling Stone magazine’s all-time greatest lists—are fundamentally shaped by cultural politics and group-think. But Russell’s list of old-time recordings in Rural Rhythm is, simply and profoundly, the work of one person uninfluenced by considerations other than the opportunity to articulate what he has learned from a lifetime listening to and studying old-time music; it is the work of one who has the depth and breadth of familiarity with old-time music recordings to compel us to take this list seriously and to learn from its claims.

All of the recordings celebrated in Rural Rhythm were products of commercial enterprise, recorded in various locations (rural and urban, South and North) in both makeshift and established studios and originally released to the general public on shellac discs to be listened to by their purchasers on home phonographs (and, from the mid-1930s onward, on jukeboxes). All the recordings were originally released on the common commercial format of that era—discs played at 78 rpm—and Russell settled upon that number, 78, as determining the number of old-time recordings he would select to include and interpret in his book. And what a remarkable list of recordings it is! Starting off predictably with one of the two sides recorded by Fiddlin’ John Carson in Atlanta during June 1923—the OKeh release often credited with launching the genre of commercial country music—Russell’s list takes in recordings by acts ranging from the inevitable (such as the Hill Billies, the band that gave the genre of country music its early nickname of “hillbilly music”; and Vernon Dalhart, who recorded voluminously under several pseudonyms), to the overlooked (including Smith’s Sacred Singers, an important pioneering gospel act not yet inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame), to the obscure (the Steelman Sisters, whose 1936 recording discussed in the book has not [as of September 2021] been compiled onto an album or posted online).

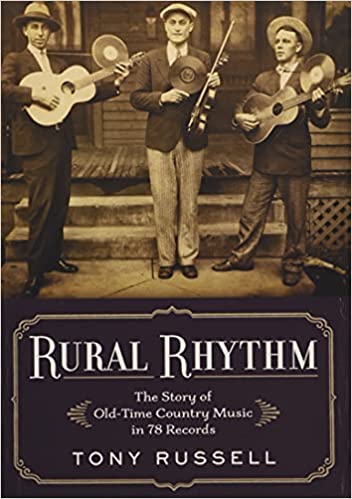

Rural Rhythm is revelatory for the way it maps out and navigates the early years of country music. For instance, while incorporating five recordings from Columbia Records’ fruitful yet overshadowed location sessions held in Johnson City, Tennessee, during October 1928 and October 1929 (the book’s striking cover image is of Byrd Moore & His Hot Shots, an act closely associated with those sessions), the list of 78 recordings in Rural Rhythm passes over all the releases from Victor Records’ ballyhooed—some would say excessively hyped—1927 recording sessions in Bristol, Tennessee/Virginia. (Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, who were “discovered” at the so-called “Bristol sessions,” made the list, but for later recordings that Russell deemed more illustrative of the distinctive artistry of those two legendary acts.) The Bristol sessions may have received an undue level of attention as the alleged “Big Bang of Country Music”—with Bristol being dubbed by government officials and tourism leaders as the “Birthplace of Country Music”—but Rural Rhythm quietly but radically retells the country music creation narrative. Selected recordings are presented chronologically in the book, with 14 seminal recordings predating the 1927 Bristol sessions. Russell offers sufficient documentary evidence to challenge any country music origin story trying to claim that the already flourishing commercial music genre began in August 1927 at those location sessions in Bristol.

To be sure, Russell’s list of recordings is strictly the skeletal structure for Rural Rhythm. The body (and indeed the soul) of the book is Russell’s interpretation—his insightful, deeply researched, and frequently witty yet always respectful expository prose in combination with evocative illustrations. Discussion of each recording combines nuanced assessment of the significance and uniqueness of that recording with salient biographical information gleaned from Russell’s resourceful efforts at “old-time archaeology”—a phrase he himself uses to describe his process of uncovering the buried stories underlying century-old recordings.

The recordings described in Rural Rhythm are all extraordinary examples of unselfconsciously revolutionary music-making by rural and mostly amateur musicians, and, inevitably, Russell’s accessible, multi-layered analyses will compel the reader to yearn to hear and compare the recordings. In that sense, Rural Rhythm can serve as “liner notes” to accompany Russell’s list of 78 recordings from old-time music’s Golden Age. The commercial “boxed set” incorporating these 78 recordings does not exist at present, and in truth it may not be justifiable since many of the recordings already appear on other CD compilations. While he himself has access to these recordings (within his own collection or via loans through the network of collectors and scholars), Russell ensures that those who do not themselves possess copies of the chosen recordings can nonetheless hear most of them. In the headnote to each recording featured in Rural Rhythm, Russell indicates available versions on previously released digital compilations and/or on two free-access online platforms (Spotify and YouTube). (And perhaps some inspired reader will take the initiative to create a Spotify playlist to match up with Russell’s book.)

Fans of old-time music will treasure Rural Rhythm, as will the large and diverse American roots music fanbase. But the book—because it possesses the integrity and authority to challenge widespread but overly simplistic and limiting notions regarding the early history of commercial country music—deserves the broadest possible readership.

Leave a Reply