Even the most utilitarian fiddle tune books carry on the stories of the musicians who played the tunes, the listeners and dancers who wanted to hear them more than once, the collectors who gathered and transcribed and edited them, the communities who thought them worth preserving. And some tune books are a story in themselves: the narrative of Harry Bolick’s unearthing of the transcriptions of WPA-era tunes collected in Mississippi Fiddle Tunes and Songs from the 1930s, Alan Jabbour’s encounters with Henry Reed documented in Fiddle Tunes Illuminated,and Newton F. Tolman’s opinionated ruminations on the New England dance repertoire in The Nelson Music Collection. Sometimes these accounts are like a walk on a back road, at the end of it a fiddler on a porch or a band in a grange hall. In this collection, lovingly researched and prepared by Frank Ferrell, well known as a performer and composer of tunes in the Northeast tradition, the road is a busy one, connecting Dudley Street in Boston with the mill towns of Lynn and Lawrence and Lowell. No surprise, really, that the book includes a tune by Gerry Robichaud called the “The Mass Pike Reel.”

As Ferrell tells it in his introductory chapters, it was Robichaud who introduced him to the playing of Tommy Doucet by way of copies of recordings Tommy and friends had made using a Wilcox-Gay Recordio disc machine, some at informal Sunday afternoon sessions at Romeo Lemay’s house. Ferrell, wanting to learn the tunes, made a copy for himself; in a story that echoes other rediscoveries of the folk revival, he had no idea at first that Doucet was alive or that he’d to meet him in the French American Victory Club in Waltham. Ferrell would be instrumental in the release of some of the recordings from the house sessions, and would record selections of the repertoire on his own album, Boston Fiddle. Doucet’s archives, including recordings made between 1939 and the early 1950s and his hand-copied collection of tunes, some of his own composition, went to Ferrell on Doucet’s death. This book is his homage to the legacy of Doucet and other Franco-American dance musicians.

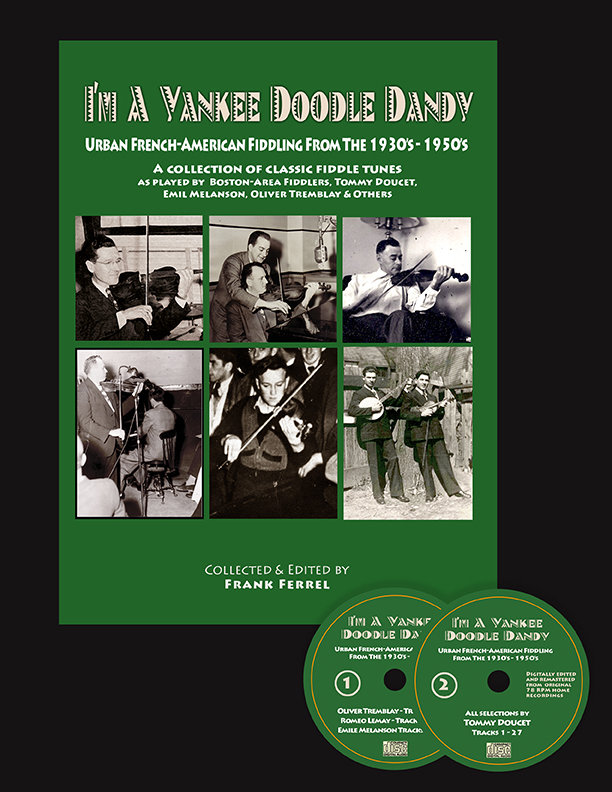

Ferrell’s book opens with a historical and personal introduction, including brief biographies and anecdotes and commentary from musicians who were Doucet’s contemporaries, some of whom are heard on the home recordings and represented in the transcriptions. Oliver Tremblay, from Quebec and a resident of Lawrence, winner of the 1939 New England Fiddle Championship and band leader of Tremblay’s French Orchestra, described Doucet’s playing as “really outstanding. In Lawrence we had some fellas that played by ear, but they were never the caliber of Tommy.” The fun of the technical challenges set by Doucet’s playing encouraged Tremblay to write tunes to match: “But when I heard a guy like Tommy play—positions and things like that, I says, ‘My God, where does he get those tunes…I’m going to invent some tunes where I can go in positions.’ So that’s how I started a writing a lot of tunes.” Multi-instrumentalist Emile Melanson played backup piano for Doucet, as well as accordion and violin. One of his venues was Roxbury’s Greenville Café, below the Intercolonial Hall, an Irish dance hall; Doucet was a regular, along with visiting musicians from Ireland and Canada. Gerry Robichaud, then a teenage prodigy on fiddle, adds a story about Doucet introducing himself by saying, “You’re the guy I’ve wanted to meet,” because he’d heard Robichaud on the radio in New Brunswick and wanted to learn the tune he’d played. Mixed in with these sketches of people and places and with the tunes that follow are images of the musicians, of their music manuscripts, of the towns they lived in, of Ted Williams at bat, of an ad for a new Chevy that could be yours for $659.

“I used to play some pretty tough tunes,” recalled Doucet, and that’s a fair enough description of the varied gathering of reels, jigs, hornpipes, and clogs, as well as a few popular melodies and waltzes, even a “gimmick duet” arrangement of “He’s a Yankee Doodle Dandy.” Some were taken from well known collections such as Cole’s 1,000 Fiddle Tunes, some learned from other musicians, and some from the radio—while some were originals. Doucet, Ferrell explains, taught himself musical notation using a tune book borrowed from a friend, and this ability encouraged him to acquire more sophisticated technique and a varied repertoire. Flair and flexibility were part of his appeal as a musician. Many of the tunes are in flat keys; many require shifting to higher positions. And many, especially those from the J. R. Pepper collection, offer surprising minor turns reminiscent of 19th-century band music.

If Doucet’s set lists offered dancers and listeners the entertainment of his skill, showmanship, and eclectic taste, the home recordings are proof of how much he and his friends were enjoying themselves. One disc is all Doucet on fiddle with accompaniment by Emile Melanson, Hermaline Germain, and, on one track, Romeo Lemay; on the other disc, the fiddlers are Oliver Tremblay, Lemay, and Melanson. Most cuts are fiddle with piano accompaniment; there are a couple of swing tunes with fiddle and guitar, an old-time number with fiddle and harmonica, and a group arrangement of “Hot Jazz Medley.” The tunes are played from with moderate to fast tempos, and always with verve. These are decades-old recordings made with hobbyist equipment and including some spoken introductions, but the recording quality is fine for appreciating the skill and expression of these musicians, for learning tunes, for figuring out bowings and articulations, and for conveying the excitement that kicks in with the shift from one tune to the next, one of the pleasures of listening to a New England dance set. As always, the sheet music gives you the notes, but it takes the recording to get across the attitude.

Ferrell’s book is meant for practical use, with the CDs as guides to playing the tunes, transcriptions with plenty of information in a readable format, and a sturdy spiral binding so that it lies flat on a stand. More than that, it offers the opportunity to become better acquainted, as a practitioner or listener, with a tradition of fiddling that combined aural and published sources, traditional and popular materials, Maritime and New England and rural and urban influences, with spirited virtuosity.

Leave a Reply