Traditional music is central to the history of Ashe County, North Carolina. From its inception, the county has produced talented musicians, most rooted in folk and traditional forms, and many of these musicians have been able, through skill and good fortune, to reach audiences beyond the local area. Ashe County natives like Frank Blevins, Al Hopkins, Howard Miller, and G.B. Grayson all made notable contributions to the earliest days of country music. Herb Hooven, a native of West Jefferson, became an influential fiddler in the Boston bluegrass scene of the 1960s, playing with Bill Keith and the Lily Brothers. Albert Hash and Glen Neaves, who made major contributions to old-time and bluegrass music in the 1960s and ’70s, both lived in Ashe at different times. However, there were many more musicians, people who never released records or performed on stage with famous groups but who were equally vital in preserving and influencing local traditional music. Although they have never received the recognition of their more well-known contemporaries, these individuals provide an important insight into the influences that have shaped regional musical cultures.

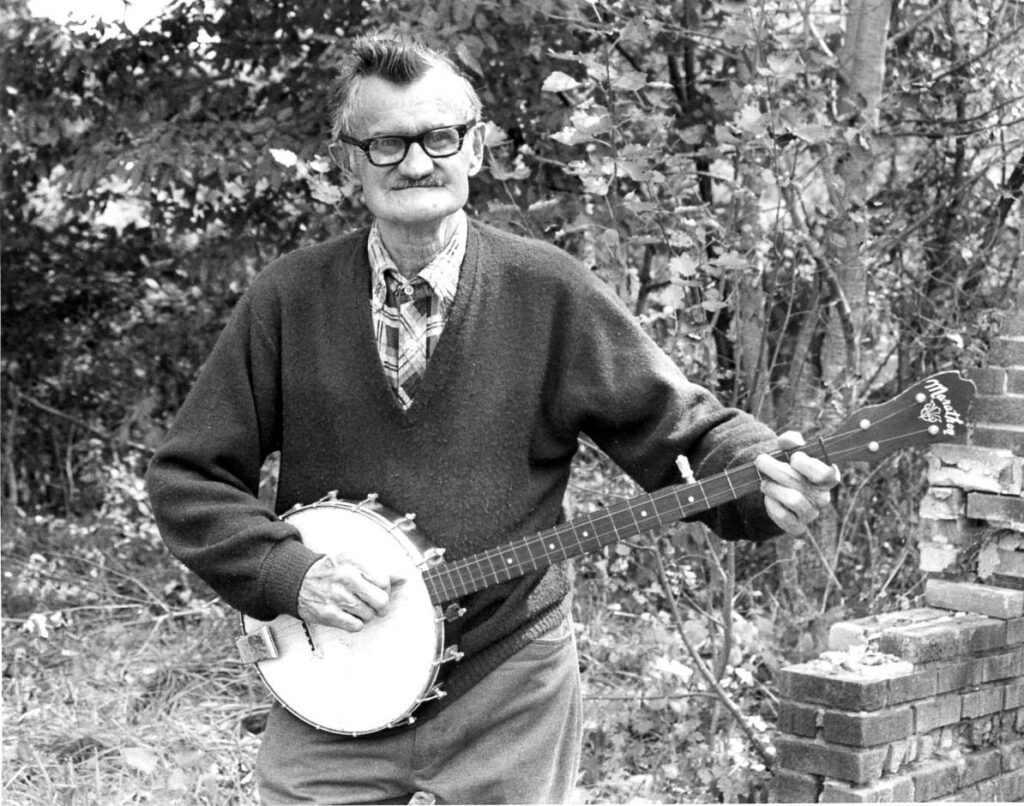

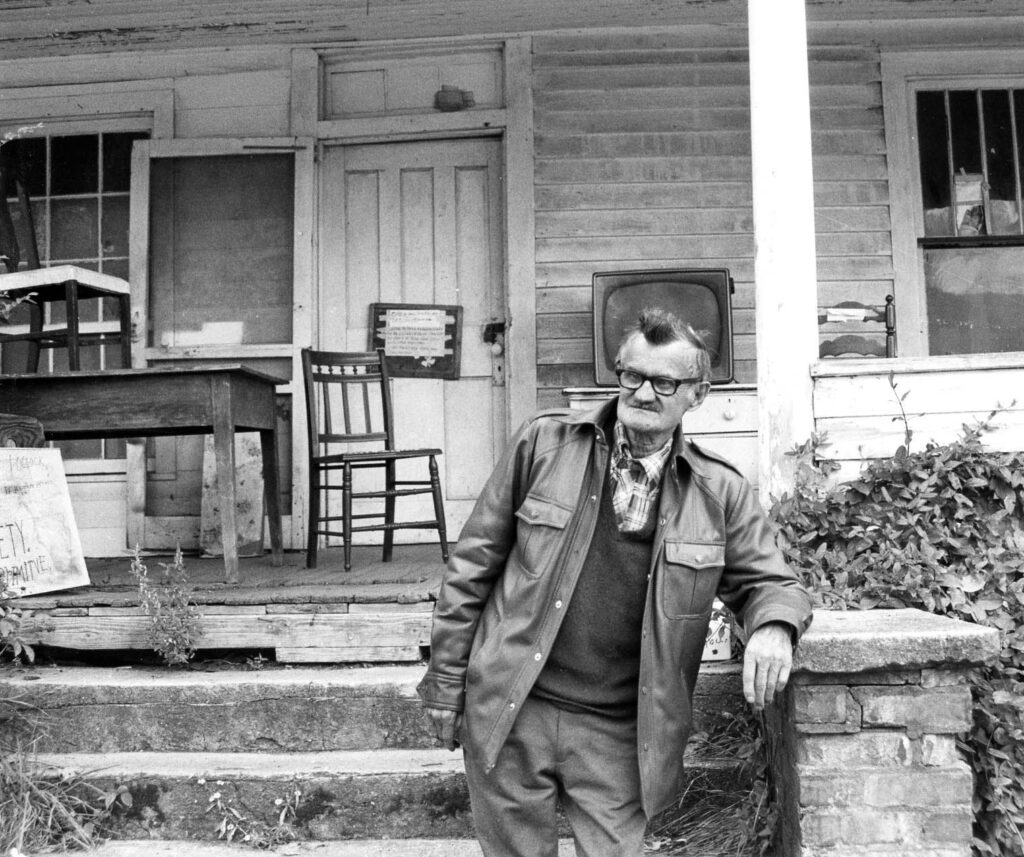

Munsey Vance Gualtney is one of these individuals. Although he was not nationally known, his influence can still be heard in the sounds of many musicians performing today. Munsey was born July 6th, 1906, in the Healing Springs community, located in the Walnut Hill district of Ashe County, an area of the county which has produced a disproportionate number of influential musicians – among them fiddler G.B. Grayson, who listed the Walnut Hill region as his birthplace on his World War I draft card.

Munsey’s mother, who was never married, was Martha Gualtney. His father, George Reece Duvall, was a neighbor who never lived with Munsey or his mother. In fact, within two years of Munsey’s birth, his father had married another local woman and begun a family with her. Because of his father’s absence, Munsey took the last name of his mother’s family and grew up in the home of his grandparents, James and Francis Gualtney.

Though it seems that no members of his immediate family were themselves musicians, Munsey was interested in music from an early age, and he soon began playing with the help of neighbors. As he would later recall, “I cut my teeth on the five-string banjo and wore them out on the fiddle; that’s the reason I don’t have any.” Almost all of Munsey’s early musical influences were women, demonstrating the often-ignored role female musicians have played in shaping traditional music. He became interested in the fiddle because of his neighbor, Nancy Blevins Baker. Known locally as “Nannie,” and 56 years Munsey’s senior, she was renowned as one of the finest fiddlers in the region. She was also a colorful figure remembered for smoking a clay pipe, and it has been suggested that some in the community may have characterized her as a witch. A regular fixture at local square dances since the Civil War, she was cited by Albert Hash as the composer of “Nancy Blevins,” a locally common fiddle tune.

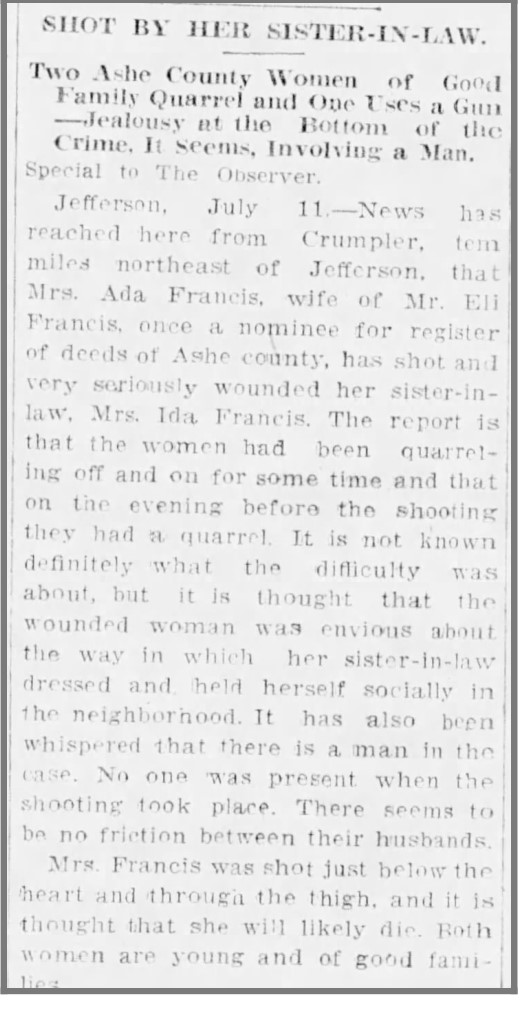

Munsey Gualtney also developed an early interest in clawhammer banjo from watching Ida Francis, Nancy Baker’s oldest daughter. According to Munsey, Baker passed on her musical talents to her eight children, almost all of whom learned to play an instrument. Like her mother, Ida Francis had some local notoriety. In 1908, she was involved in a violent altercation in which she was shot by her sister-in-law Ada. According to a newspaper report from the time, Ida had become “envious about the way in which her sister-in-law dressed and held herself locally in the neighborhood.” The account goes on to conjecture that it “has also been whispered that there is a man in the case.” This disagreement resulted in a fight which quickly escalated. Although her wounds were at first expected to prove fatal, Ida, shot through the chest, miraculously was able to recover from her injuries, and she went on to inspire young Munsey Gualtney to pick up the banjo.

Luckily for Munsey, his home in Healing Springs was ideally located for launching a musical career. Besides having ready access to musical neighbors, the area provided a unique opportunity for regular performance. The twin resorts of Shatley Springs and Healing Springs, both of which attracted tourists for their reputedly medicinal waters, were only a few miles from Munsey’s house; through the summer months, both resorts provided a ready audience for aspiring musicians from the local community. By his teenage years, Munsey had teamed up with Glen Neaves, another native of the Walnut HIll region, and the two began playing to entertain tourists at Shatley Springs on weekends. Neaves, who would go on to record three traditional bluegrass albums on the Folkways label with his band the Virginia Mountain Boys, would later recall in an interview that these performances with Munsey were a highlight of his young playing career. He recalled, “I played every Saturday night there when I was just a kid for those people – square dance. We played in the old spring building they called it. The railroad engineer’d been retired. He had an old derby hat and he’d pass it around for us kids. We liked that pretty good too.”

By the late 1920s and early ‘30s, traditional Southern folk music had been propelled out of local communities through records and radio. Suddenly, musicians who would historically have been confined to playing for local dances and community gatherings were able to reach wider audiences through commercial recordings. These recordings allowed musicians, many of whom up to that time had played largely regional repertoires, to learn new styles and tunes not native to their area. Like many other fiddlers of his generation, Munsey was quickly attracted to records by groups from Georgia, notably the Skillet Lickers and Clayton McMichen’s Georgia Wildcats. Although exposure to these new sounds caused a drastic shift of personal style and tune repertoire for many musicians of the 1920s and ’30s, Munsey’s remained largely unchanged. Despite exposure to these recordings, he continued to rely frequently on cross tunings and preserved many archaic regional pieces in his playing repertoire throughout his life.

Although Munsey Gualtney would never become a fully professional musician himself, the ‘30s allowed him to gain greater familiarity with the life of a touring musician. By 1930, he had a new neighbor who would help him move from playing for weekend square dances and local resorts to playing for wider audiences: Henry Whitter, one of the first musicians ever to release a commercial country recording. Whitter had moved to Healing Springs after marrying his fourth wife, Hattie Baker, who was a granddaughter of Nancy Blevins Baker.

In the early ’20s, Whitter, by virtue of being one of the first artists to record country music, had been a dominant musical force. In a single 17-month period between 1924 and 1925, he recorded 38 different songs for the Okeh label. In the late 1920s, as more polished performers entered the recording arena, Whitter had been able to continue his career by partnering with fiddler and singer G.B. Grayson. However, by the 1930s, the deepening Great Depression, Grayson’s untimely death, and the advancing talents and changing styles of new groups had ended Whitter’s recording career. With no other means of making money, Whitter still sought to secure a regular income through live musical performances. Following Grayson’s death, Whitter began enlisting the aid of younger musicians in Ashe County to assist him. Along with other young fiddlers like Albert Hash, Alonzo Black, and Worth Taylor, Munsey Gualtney got an early taste of show business with Whitter. Whitter would go on brief local tours, singing songs he had recorded in the 1920s, while Munsey would provide instrumental accompaniment. Together, he and Whitter played local schoolhouses and gatherings, usually charging around 25 cents for admission. Whitter was cited as an important early influence by many of the young fiddlers who were able to accompany him at his local performances, but his tendency to take advantage of their youth and inexperience sometimes led them to set out on their own quickly. Alonzo Black once told an interviewer, “I played with [Whitter] for about a year, and when we got money he wouldn’t give me a dime of it. We went to Chapel Hill, to what they call the Dogwood Festival, me and him…They give [Whitter], I believe it was forty dollars, but he didn’t give me and that boy a dime of it, and he quit and I quit.”

Around the same time that he was touring local school houses with Henry Whitter, Munsey became a member of a band of musicians closer to his own age. The group consisted of his younger half-brother Lee Duvall, brothers Fred and Worth Taylor (who had also spent time touring with Whitter), and a young banjo player, Gladys Calloway. The group called themselves the Carolina Ridge Runners (not to be confused with the North Carolina Ridge Runners, another group from Ashe that released a record on Columbia in the 1920s). Together these young musicians played local dances and gatherings and made a brief appearance on WOPI, a Bristol, Tennessee, radio station founded in 1929.

Despite his talents and experiences, Munsey, like many folk musicians of his era, was never able to make a full-time career out of music. The banjo and fiddle were to him pursuits of pleasure rather than profession. During the time he was playing weekend dances, he was struggling to make a living laboring on the farm of his grandparents, James and Francis. Later, Munsey would transition to more industrial work, laboring in a cotton mill and for the Norfolk and Western Railway. Eventually, he opened a small shop in the town of Jefferson and sold antiques. Throughout these changes of career, he continued to play, maintaining the same general style and repertoire he had developed in the late 1910s and early ‘20s. As Munsey aged, new musical styles like bluegrass and Western swing greatly redirected and reshaped local music, eroding traditional song canons and playing techniques and introducing more modern sounds and rhythms. Munsey, who had begun his life in Ashe County’s dominant musical culture, was quickly becoming a relic of the past.

Despite these changes, his love of music never dissipated. Even into their 60s and 70s, Munsey and the other members of his first band, the Carolina Ridge Runners, gathered regularly to play. Through the 1970s and into the ‘80s, he was a regular participant at local jam sessions and could be found playing at the old hospital in Jefferson on Thursday evenings and at the Beaver Creek Cannery on Saturday nights. Ironically, this later stage of his life, far removed from the square dances and performances of his youth, was probably the most important period for securing his legacy. Even though these venues and jam sessions were small and informal, they allowed Munsey to interact with a wide variety of younger local musicians, passing his influence on to others. Thornton Spencer, who often attended jams with him, would learn many of the more archaic pieces Munsey continued to play. Thornton learned tunes like “Picking out the Devil’s Eyes” and “Sally was a Poor Girl,” and then passed them along to still younger musicians living in Ashe County today. Munsey was one of the last fiddle and banjo players in Ashe County to bridge the divide from the pre-recording era. Through him, new generations of musicians in the 1970s and ’80s were able to make first-hand contact with a regional style and repertoire which had been steadily fading.

Munsey Gualtney died on March 20, 1988. Other than two tracks featuring his fiddle playing on Rounder’s Old Originals, Volume Two, he was never commercially recorded. However, his influence on old-time music has been immense. Musicians like Albert Hash and Glen Neaves, two of the region’s most well-known old-time artists, gained early experience playing with Munsey. Other musicians like Thornton Spencer served as a bridge to younger fiddle and banjo players, allowing Munsey’s tunes and stories to persist years after his death. Thanks to this, hoary old fiddle and banjo pieces that likely would have been swept away by the homogenizing power of recorded music were able to survive. Munsey Gualtney, like so many other musicians of his era, served to keep the traditional folk culture alive, not through his fame or his albums, but solely through his love of music.

Josh Beckworth is from Crumpler, North Carolina. He is the president of the Ashe County Historical Society and author of the book Always Been a Rambler: G.B. Grayson and Henry Whitter, Country Music Pioneers of Southern Appalachia available through McFarland Publishing. He currently teaches English and Appalachian Studies at Ashe County High School.

Sources for this article include “Interview with Albert Hash,” February 5, 1976, Appalachian State University Digital Collections; an interview with Alonzo Black by Ronnie Taylor, July 22, 1975; an interview with Munsey Gualtney by Frank Weston, September 30, 1982; and the liner notes to Virginia Mountain Boys Vol. 3. (Folkways, 1974).

Leave a Reply