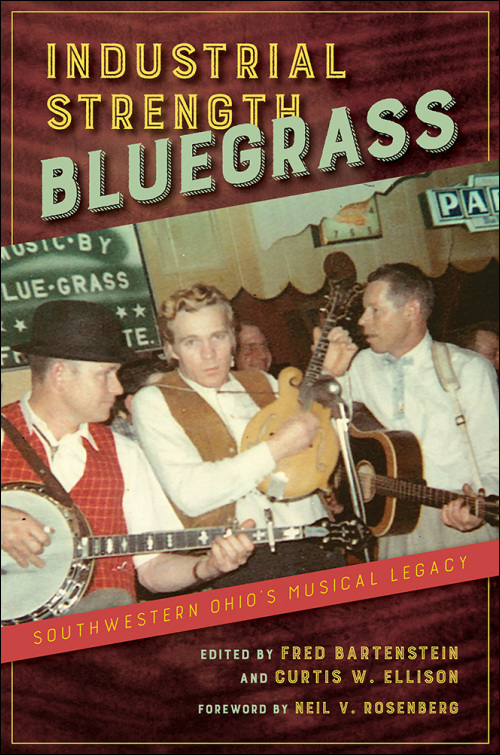

Industrial Strength Bluegrass: Southwestern Ohio’s Musical Legacy

Fred Bartenstein and Curtis W. Ellison, editors

Ohio is not the first place that comes to mind when one thinks of bluegrass music. However, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, southwestern Ohio became a stronghold for the style. Industrial Strength Bluegrass: Southwestern Ohio’s Musical Legacy, published in 2021 by the University of Illinois Press, collects a series of essays that explain how this region developed a thriving bluegrass scene that both attracted and fostered its own national touring bands, such as the Osborne Brothers, the Hotmud Family, and others.

Industrial Strength Bluegrass straddles the line between academic research and anecdotal memoir, with authors that range from scholars and regional historians to musicians and disc jockeys who were part of the bluegrass musical community in Cincinnati, Dayton, and the surrounding suburbs. These contributors provide a well-rounded portrait of a community that was built on a foundation of Southern migrants, particularly from Kentucky and West Virginia, who moved north during the 1930s and ‘40s to find work in Ohio factories and the proliferation of “barn dance” radio programs on local stations, including WLW, WCKY, and WPFB.

These migrant families brought their folk traditions with them, including a love for old-time and country music that contributed to the popularity of such programs as Renfro Valley Barn Dance and Boone County Jamboree, which eventually led to the establishment of successful recording label King Records in Cincinnati. The growing enthusiasm for country music and bluegrass in particular resulted in a sold-out performance of Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys in 1947 at Memorial Hall in Dayton, which served a kind of “big bang” moment for the region’s bluegrass scene.

Industrial Strength Bluegrass features 11 essays, edited by scholars Fred Bartenstein and Curtis W. Ellison. Highlights include “All the Way to the Fence: Bluegrass Broadcasting,” by journalist and radio host Daniel Mullins, who details the vibrant bluegrass programming on radio broadcasts throughout the Miami Valley, including the legacy of his own family, with grandfather Paul “Moon” Mullins and father Joe Mullins, who were prominent DJs in the region.

Mac McDivitt’s “Taking the Music Home: Bluegrass Recording Studios” provides a robust history of the myriad record labels, both large and small, that dotted the landscape throughout southwestern Ohio, including Syd Nathan’s King Records, Earl T. “Bucky” Herzog’s Radio Artist Records, Lou Ukelson’s Vetco Records, and more than a dozen others.

Rick Good, founding member of the Hotmud Family, writes about a short-lived community hub in his essay, “The Living Arts Center’s East Dayton Roots.” The facility offered music classes and programming for the region for 10 years during the 1970s.

While bluegrass is obviously the focus of this collection, there are some interesting tidbits for old-time music fans, including in Jon Hartley Fox’s “Buckeyes in the Briar Patch: Southwestern Ohio Bluegrass in the 1970s,” which dedicates a section to old-time string bands and musicians active in the region, most notably Fiddlin’ Van Kidwell, who recorded two albums backed by the Hotmud Family for Vetco Records.

Others essays focus on Appalachian migration, gospel influences, bluegrass venues in the region, the intersection of bluegrass music and urban Appalachian identity, and the unique characteristics of the bluegrass that originated in southwestern Ohio. Overall, Industrial Strength Bluegrass provides a fascinating and easy-to-read history of a distinctive musical community, and how and why it came to be.

Leave a Reply