“The old tunes, like the old originals, they are all about gone.” This is the way fiddler N.H. Mills of Boones Mill, Virginia, put it to us that summer day in 1973. He was referring to the old-growth chestnut trees that had been killed off by disease during the 1920s and ‘30s, the “old originals” he called them. And I guess he considered the new music, whether it was bluegrass or country, as a similar kind of blight, slowly but surely killing off the old music, the fiddle tunes and songs he had known all his life. The tree analogy resonated with us, for back in the late 1960s and early ‘70s it did seem that the traditional music of the Southern mountains was slowly disappearing, replaced by new sounds coming in on radio, records, and TV. We were wrong, of course; the music seems stronger now than ever. But at the time, without the benefit of foresight, we felt a pressing need to record as much of it as we could before it all ended.

The New Lost City Ramblers led the way. Not only did they insert old-time music into the folk revival and introduce so many of us to the likes of Charlie Poole, Gid Tanner, and Uncle Dave Macon, but early on Mike Seeger and John Cohen began to seek out the performers on the old records, folks like Dock Boggs, Maybelle Carter, and Eck Robertson, and introduce them to city audiences. Others followed: Ralph Rinzler scouted out Clarence Ashley and in the process met Doc Watson; Charlie Faurot and Dave Freeman went looking for Ben Jarrell of DaCosta Woltz’s Southern Broadcasters and instead found his son Tommy. And then there was Alan Jabbour, whose fieldwork throughout the Upland South and particularly with fiddler Henry Reed not only fed material to his Hollow Rock String Band bandmates but also inspired others to do the same. The idea was to head out and visit traditional musicians, learn to play like them, and then bring the music back home to teach to your friends. Or in some cases, to stay on and live the mountain life! I’m thinking here of people like Ray Alden, Bruce Greene, Paul Brown, Andy Cahan, Alice Gerrard, Brad Leftwich, and Linda Higginbotham, to name just a few among many who became both players and collectors.

I knew the drill a little from my college days in Rhode Island. I had done an ethnomusicology paper on a fiddler from Vermont and then visited and recorded a family of fiddlers in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, but the player/collector thing really started for me when I moved to Chapel Hill during the summer of 1971 to start folklore graduate school. I moved into an old house in Hollow Rock and began playing banjo with the Fuzzy Mountain String Band, a kind of loose jam band whose members were fully committed to the “find it and play it” ideal. This was what the Fuzzies were all about, and I spent many a long weekend with Malcolm and Blanton Owen at Tommy Jarrell’s, fetching Fred Cockerham for a session, eating tomato sandwiches at Kyle Creed’s store (and buying a banjo), sleeping in a freezing truck outside Taylor Kimble’s, and being surprised that the famous Gaither Carlton was eager to sit down and play with me. It was all great fun.

But I was in folklore school and a historian by nature, and for me there was an academic side to it as well. The music fascinated me, and I was curious about where it had come from, how it varied over time and space, and what it all meant. It wasn’t rocket science to figure out that Patrick County, Virginia, playing was not the same as music in Low Gap, North Carolina, or Galax, and it seemed like the place to start lay in mapping out the various local styles within the central Blue Ridge. And then there was the history thing, which was puzzling. Joe Caudill, an 87-year-old fiddler from Ennice, North Carolina, started it all by telling me that he didn’t play the old-time music that his father Sidney had played. “These new tunes,” Joe told me late in 1972, “they wasn’t in style when he was playing. Tunes we play now, back in his day, he didn’t play them.” By new tunes he meant dance pieces like “Sally Ann,” “Holliding,” and “Pretty Little Gal,” which he distinguished from older more complex tunes like “Piney Woods Girl,” “Belles of Lexington,” and “Waves on the Ocean.” I started asking more questions, visiting others like Joe’s older brother Huston and their neighbor Luther Davis, who backed up Joe’s chronology. It seemed that in the old-time music I knew there were both old and new tunes and I thought it would be worthwhile to figure out what had happened. Alan Jabbour had just introduced me to the Emmett Lundy recordings at the Library of Congress and these, made in 1941 when Mr. Lundy was in his 80s, provided the best evidence of what the old-style Galax playing was like. I just needed a better idea of what had changed when younger players, those I was meeting who were then in their 70s and 80s, had been learning.

My professor at the University of North Carolina, Dan Patterson, urged me to apply for a youth grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. This would have been in the winter of 1972. I proposed a survey of musicians in a four-county study area along the central Blue Ridge, with a goal of identifying the main stylistic subregions while at the same delving more deeply into the music’s history. The plan was to systematically cover a defined geographic area, recording as many players as possible, and see what patterns emerged. Remarkably, I got the grant, and it was a lot of money for those days. I had included my friend and banjo mentor Blanton Owen in the project, so there was enough for both of us to move to the mountains – Blanton to Sparta, North Carolina, where he could cover the west side of the study area, and me the east. I first lived “down the mountain” in a primitive log cabin (no water, power, or plumbing) in Claudville, Virginia, outside Stuart. But by late August of 1973 my wife and I had moved up to a real house in Meadows of Dan. Wearing overalls and heating with wood were mandatory!

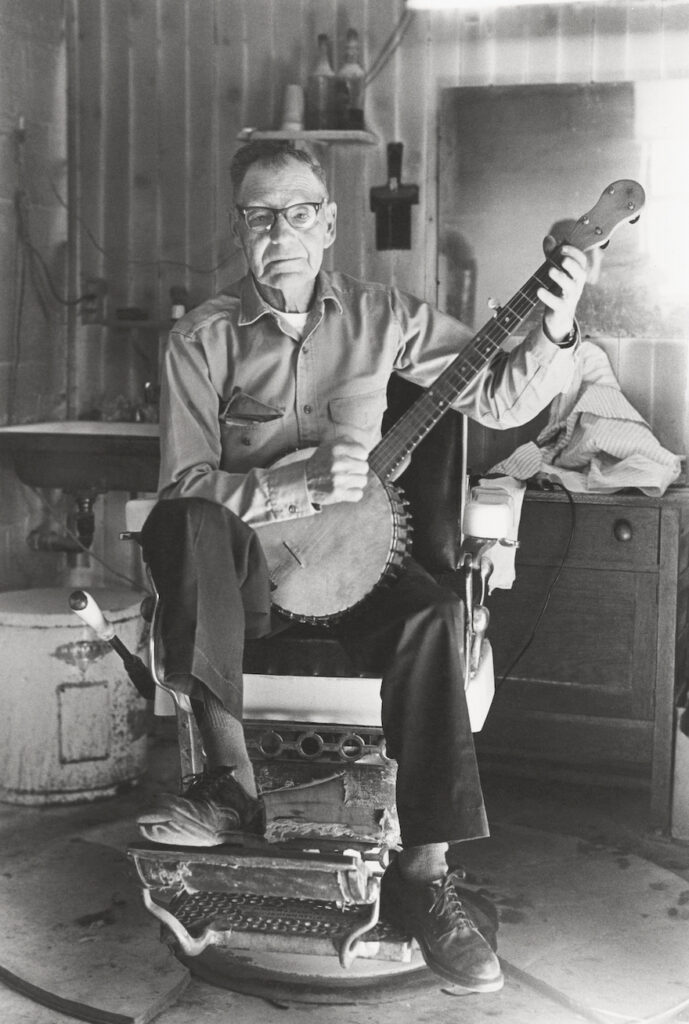

By late summer Blanton and I were busy visiting and recording various musicians. We continued hanging out with Tommy, Fred, and Kyle, but branched out, following up leads on a wide range of players. Some of the most memorable ones for me are hardly household names today, but each brought something special to the project. There was Frank Dalton, my barber (he “cut by hat size”) and a fine clawhammer banjoman (this is how locals said it). Frank played G tunes, which was rare (he used the gGADE tuning) and dropped his thumb over to the third string which was also something we didn’t see very much. I also loved my sessions with Dent Wimmer and Sam Connor, who played some great music but also lived down the road in Floyd County from three bachelor brothers, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego (seriously!). And then there were the Spanglers from Meadows of Dan. Wallace Spangler, who had died in 1926, had been sort of the Emmett Lundy of Patrick County. He left no recordings but was remembered in the music of players like Jesse and Pyrus Shelor of the famous Shelor Family, two sons, J.W. (Babe) and Charles (Tump), and a nephew Dudley (also called Babe). Tump was 90 and had a hard time playing but wanted to give me some of Wallace’s tunes, so he hummed or “doodled” them, and with his rich baritone voice these are some of my favorite recordings. And then through a wonderful local guitarist, Maggie Wood, I got hold of some home recordings of the two Babes. I convinced Dave Freeman to put them out on his County label.

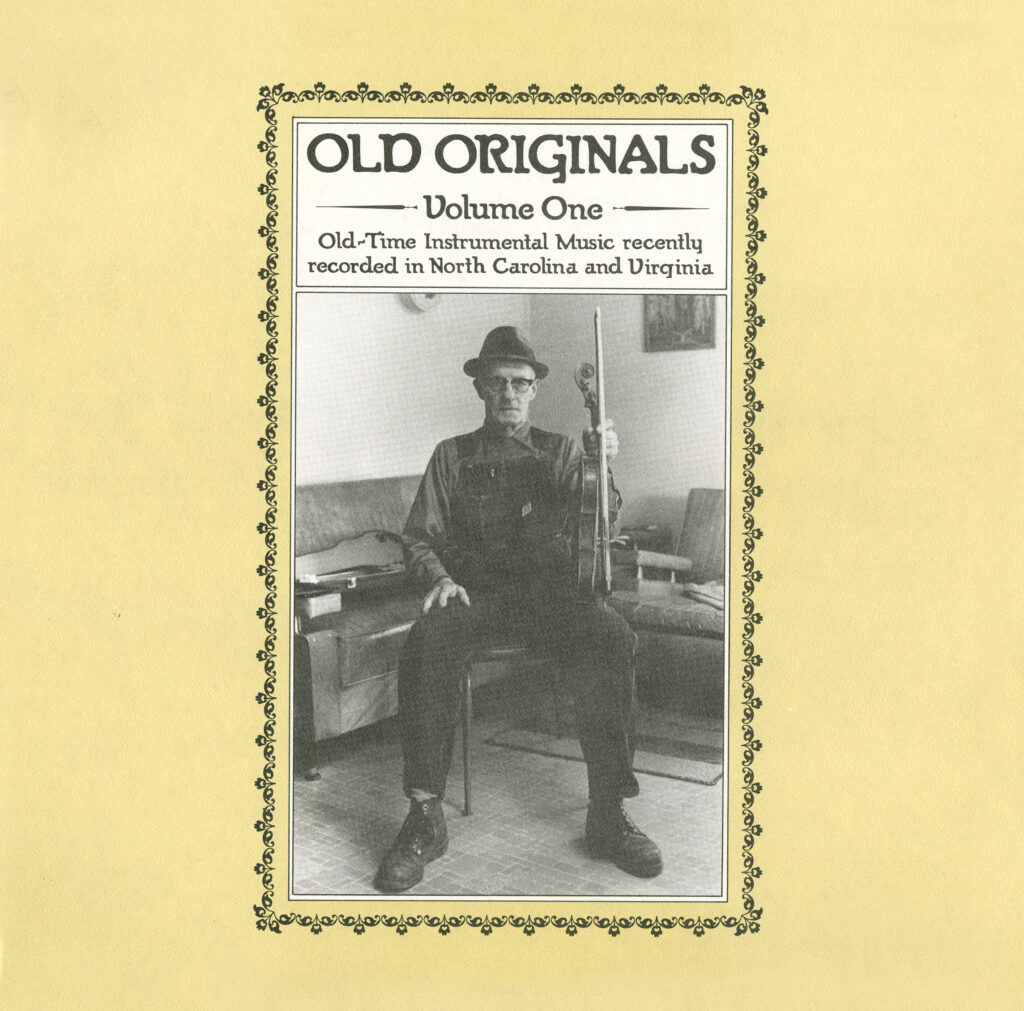

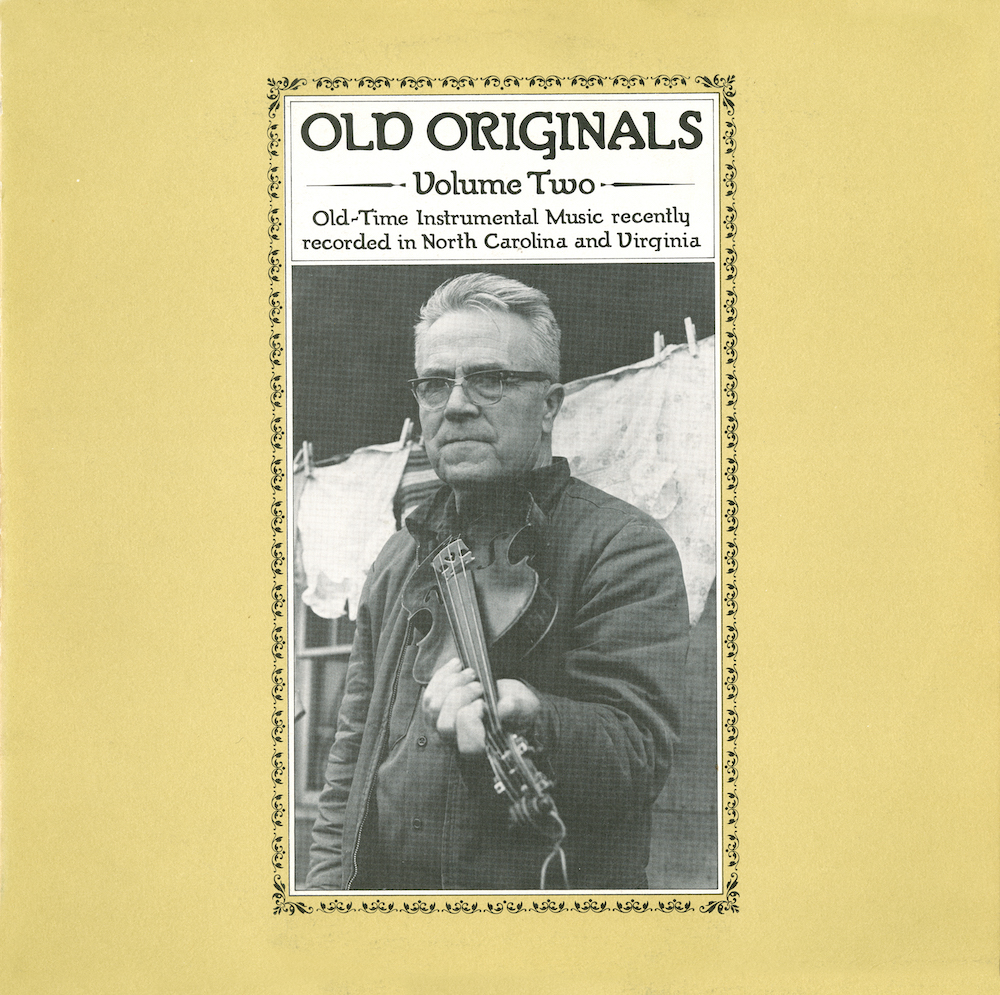

I think one of the reasons I got the government money was because Rounder Records (who we knew from the Fuzzy Mountain days) had agreed to issue LPs of our fieldwork discoveries. The person we worked with was Bill Nowlin, and I must thank him for greatly supporting the project. With him we produced, using Mr. Mills’ tree reference for the title, the two-volume The Old Originals: Old-time Instrumental Music Recently Recorded in North Carolina and Virginia (Rounder 0057 and 0058) set. Volume 1 (Fig. 9) featured players I found in Patrick and parts of Floyd and Franklin counties, while Blanton assembled the second (Fig 10), covering Carroll and Grayson Counties.

The Old Originals records focused primarily on outlining and describing subregional traditions; the history question I tackled in a separate project which involved writing the notes for the Emmett Lundy LP I produced in 1976 with the eminent old-time music scholar Tony Russell. I’m not sure how it happened, but somehow Tony found out I was looking to issue these seminal recordings and he agreed to put them out on his London-based String label. The notes read like the Indiana University term paper they were, but basically in them I tried to explain how the music had changed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I blamed it all on the banjo, which hasn’t always gone over so well with banjophiles (one almost punched me at the Breaking Up Winter festival!). But I was convinced then, and remain so today, that as the fiddle-banjo ensemble/band gained in popularity, older more individualized and complicated tunes slowly dropped away. These tunes didn’t fit either the more formulaic and rhythm-driven band style or the limited melodic capabilities of the fretless banjo. At the time, I didn’t have the musical training to back up my hypothesis, but years later I convinced my friend and fiddle-ologist Tom Sauber to help me lay it out more clearly in the essay “’I Never Could Play Alone’: The Emergence of the New River Valley String Band, 1875-1915,” in the book Arts In Earnest: North Carolina Folklife (Duke University Press 1990).

All this holds for only the small section of the Blue Ridge we worked in, and who knows how it might apply to other parts of the South. I’m not sure anyone cares much about these things. The music itself is what’s important. And this is as it should be. I remain curious, however, and do hope that more of the “Revival of the Revival” players will ask questions about the music’s history, both past and present.

Tom Carter went on from Meadows of Dan to finish his studies at Indiana University’s Folklore Institute. He ended up back in his native Utah teaching architectural history, but misses the Blue Ridge greatly.

Leave a Reply